Author: Gani Nasirov | www.ganinasirov.com

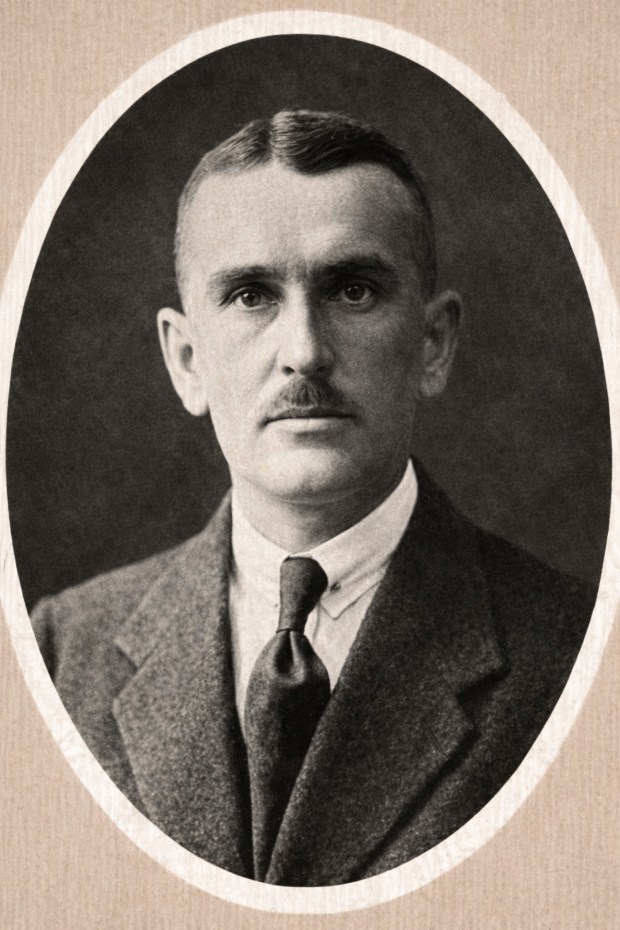

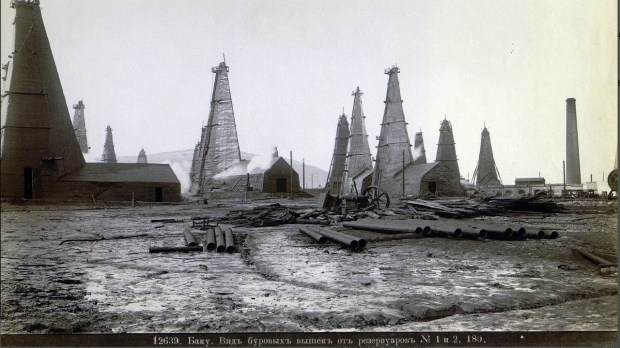

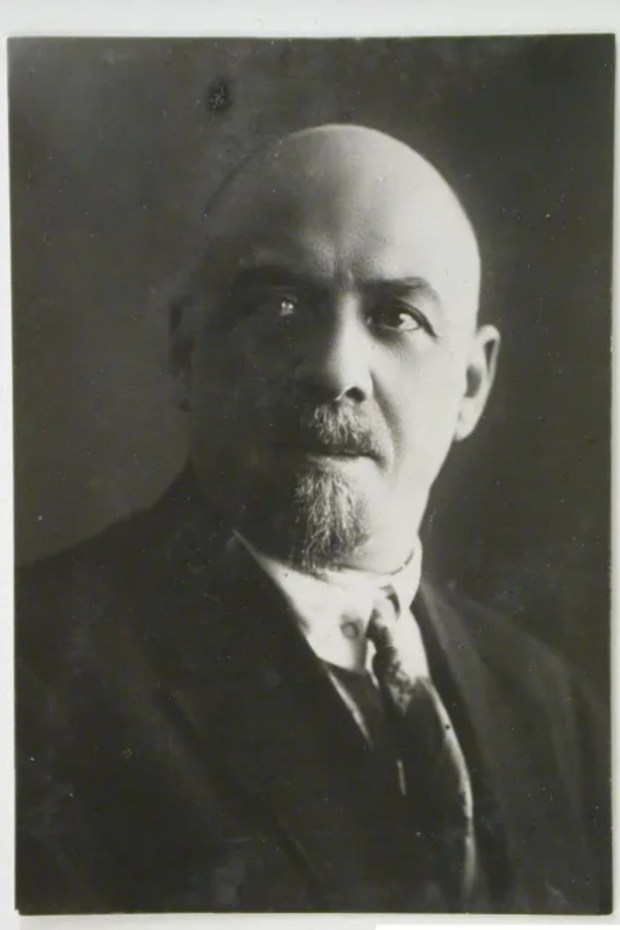

When Aleksandr Serebrovskii arrived in the United States in the summer of 1924, the Baku’s oil industry was in a fragile state. Production had fallen far below its pre-revolutionary peak, equipment was worn and outdated, and the once-celebrated oil fields of Baku were struggling to meet the demands of the newly established Soviet state. For Serebrovskii—an engineer by training, an administrator by necessity—as the head of ‘Azneft’ (The Azerbaijan Oil Committee ‘Azneftkom’ was established to nationalize the Azerbaijani oil industry in may 1920. A few months later, it was replaced with Azerbaijan State Oil Industry Union, ‘Azerneft’ Trust) the journey was not diplomatic. It was a practical mission, driven by urgency and shaped by a firm belief that Soviet industry could be rebuilt through the selective adoption of the world’s most advanced technologies.

From the outset, his itinerary reflected that pragmatism. Within days of landing in New York, Serebrovskii was received at the headquarters of Standard Oil, where senior executives granted him rare access to oil fields, refineries, and technical operations across the country. At a moment when relations between Soviet Russia and American corporations were still marked by caution and suspicion, this openness suggested a shift: cooperation grounded less in ideology than in shared industrial interest.

Access, however, did not solve Azneft’s most pressing problem—money. The Soviet oil trust of Azneft (nationalization of all private oil businesses enacted in May 1920) had no foreign currency reserves and no access to international credit. American suppliers were willing to sell drilling and refining equipment, but only with reliable guarantees of payment. Faced with this impasse, Serebrovskii made a calculated gamble. He wrote directly to John D. Rockefeller (Founder of the Standard Oil Company).

An Unexpected Door Opens at Standard Oil

The meeting that followed, held at Rockefeller’s country estate, has the feel of a historical anomaly. An aging titan of American capitalism received a Soviet oil administrator not as a political adversary, but as a fellow industrialist. Serebrovskii later recalled the simplicity of the house, the long walks through the park, and Rockefeller’s attentive questions about Baku and its oil reserves. In the end, Rockefeller agreed to provide letters of guarantee to banks and suppliers, effectively underwriting Azneft’s purchases. The decision rested not on sympathy for Soviet ideology, but on personal trust—on Rockefeller’s assessment of Serebrovskii as disciplined, modest, and unlikely to squander borrowed resources.

With this obstacle removed, the journey accelerated. The “red director” (that is how Americans called Serebrovskii) traveled through Pennsylvania’s early oil towns, California’s rapidly expanding fields, and Oklahoma’s oil centers, including Tulsa, where he attended the International Petroleum Congress. He studied production organization, supply chains, and refining technologies, and even worked directly on drilling sites to understand the routines of American oil workers. What he encountered was an industry built on standardization, electrification, and efficiency—principles he believed could be adapted to Soviet conditions.

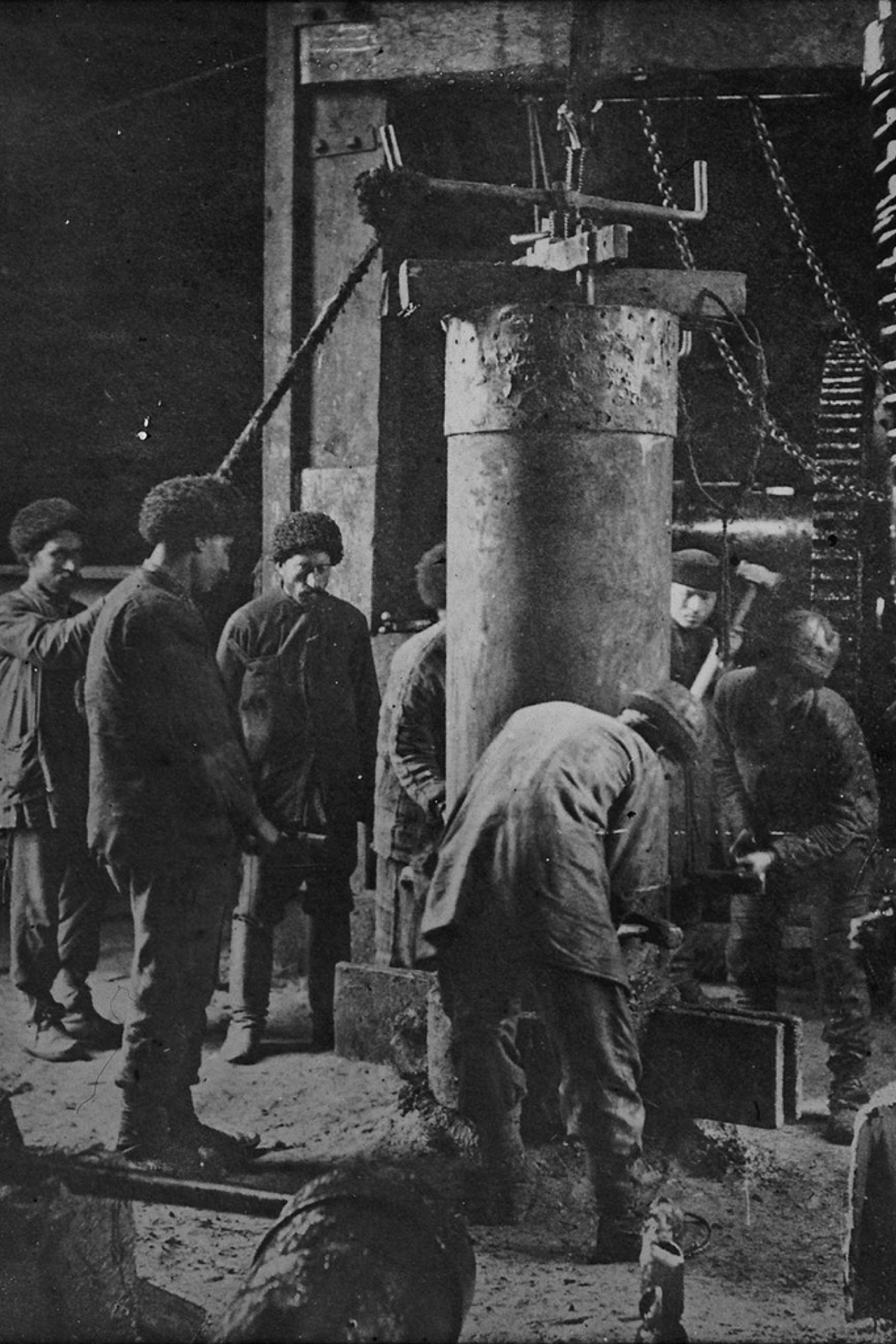

The technological consequences were swift and profound. Electric downhole pumps, rotary drilling, and modern refining processes were introduced at ‘Azneft’. Soviet oil workers referred to these innovations simply as “American,” a shorthand that acknowledged both their origin and their transformative effect. Within a few years, drilling speeds increased dramatically, production costs fell by nearly half, and oil output surged—laying the technical foundation for the Soviet Union’s industrial expansion at the end of the decade.

Yet Serebrovskii’s attention extended beyond machinery. In American oil towns, he paid close attention to how workers lived. In American oil towns, he encountered a highly rationalized housing system based on standardization, speed of construction, and cost efficiency. A notable example was the prefabricated housing produced by Sears Roebuck & Company, especially its widely marketed Honor-Bilt houses (Click to see catalog of houses). These homes were sold as complete kits, with standardized components that could be transported, assembled quickly, and adapted to different sites.

For Serebrovskii, such models offered a practical solution to the severe housing shortage faced by oil workers in Baku, where rapid industrial expansion had far outpaced the availability of adequate living space. He argued that similar prefabricated and standardized approaches could dramatically reduce construction time and costs, aligning well with the economic pragmatism of the NEP period and the broader Soviet ambition of accelerated industrialization.

“American” Became a Technical Term

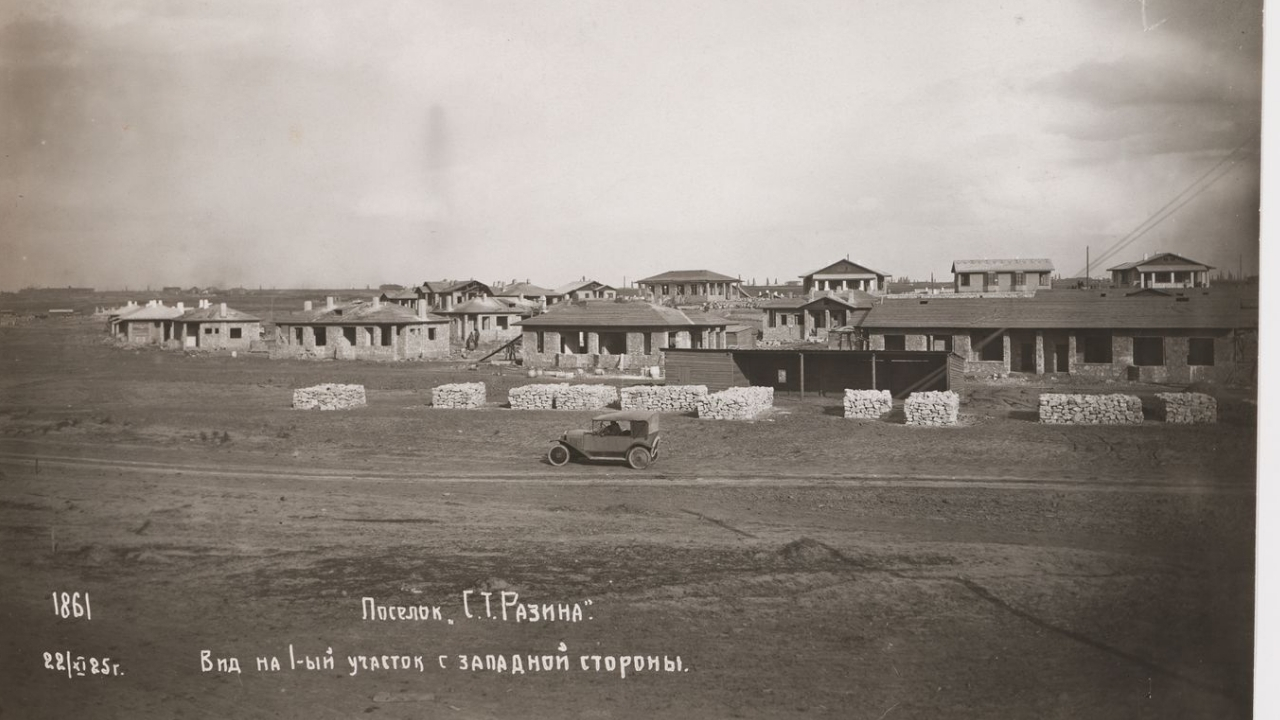

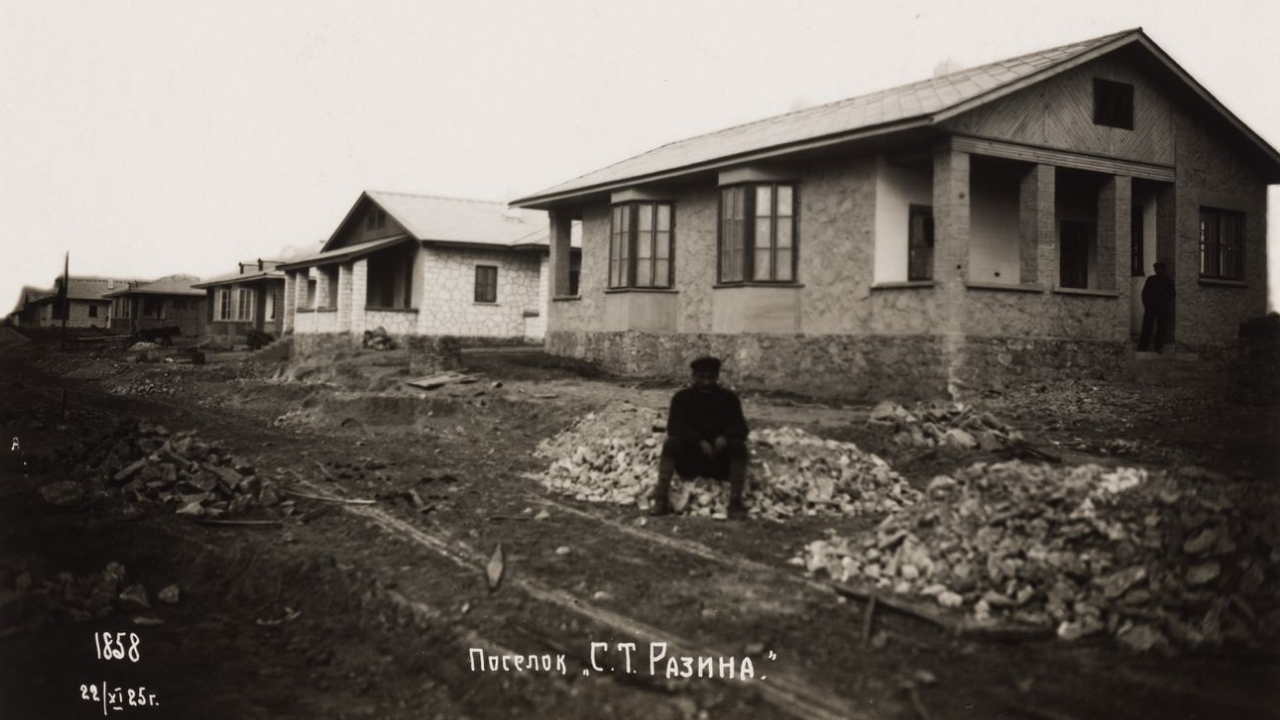

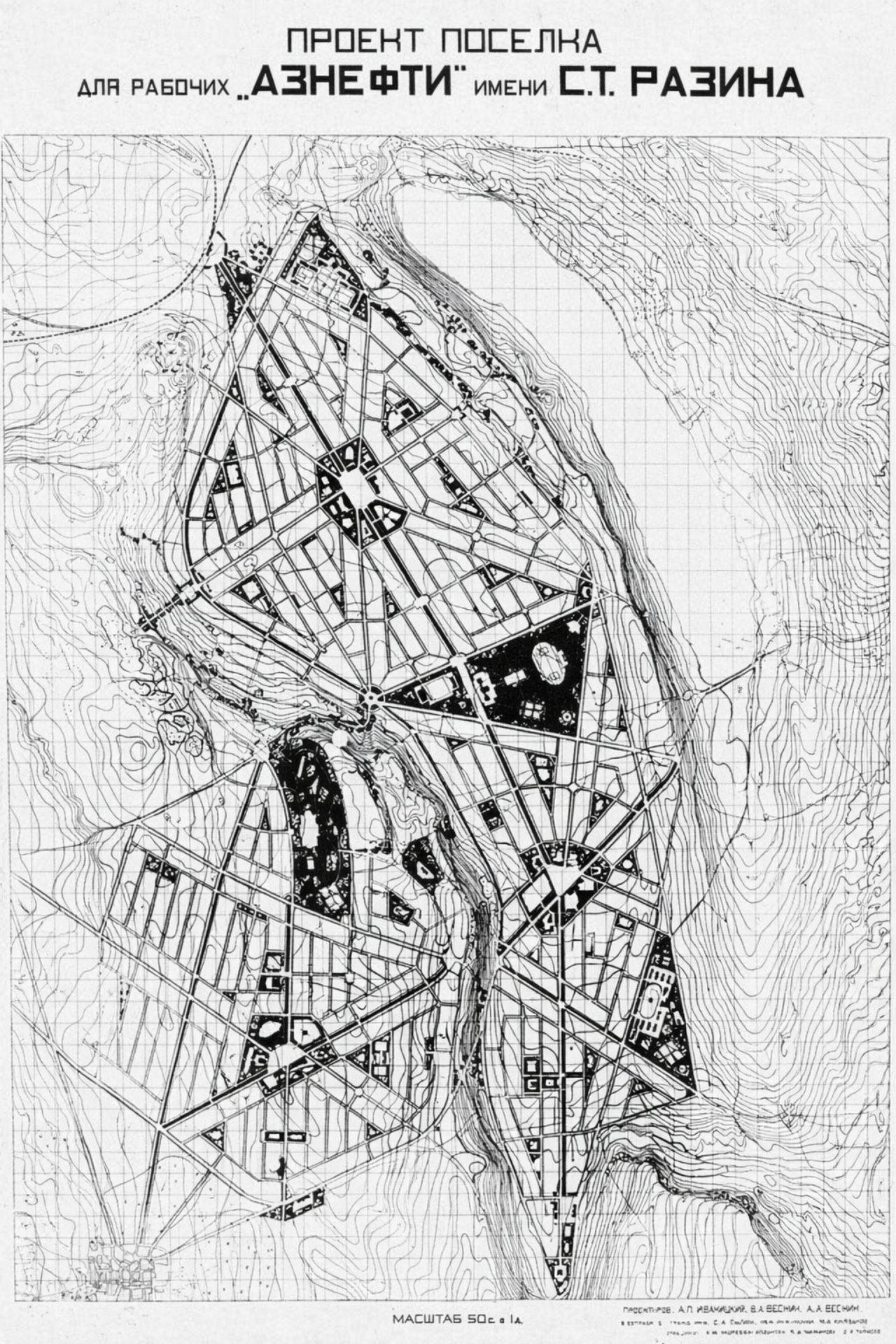

Determined to address Baku’s acute housing crisis, Serebrovskii ordered entire sets of American-style cottages for oil workers on the Absheron Peninsula. This interest in American housing methods led to a direct experiment on Azerbaijani soil. An “American” (or “Amerikanka” in popular parlance) house was constructed in S. T. Razin workers’ settlement, one of Baku’s major oil-field settlements, to test whether U.S.-style housing could be successfully transplanted to local conditions. The building consisted of single-story paired units and incorporated decorative architectural details that echoed American suburban aesthetics. Alongside structural components came objects still unfamiliar in Soviet daily life: gas stoves, washing machines, mobile clinics, and household appliances.

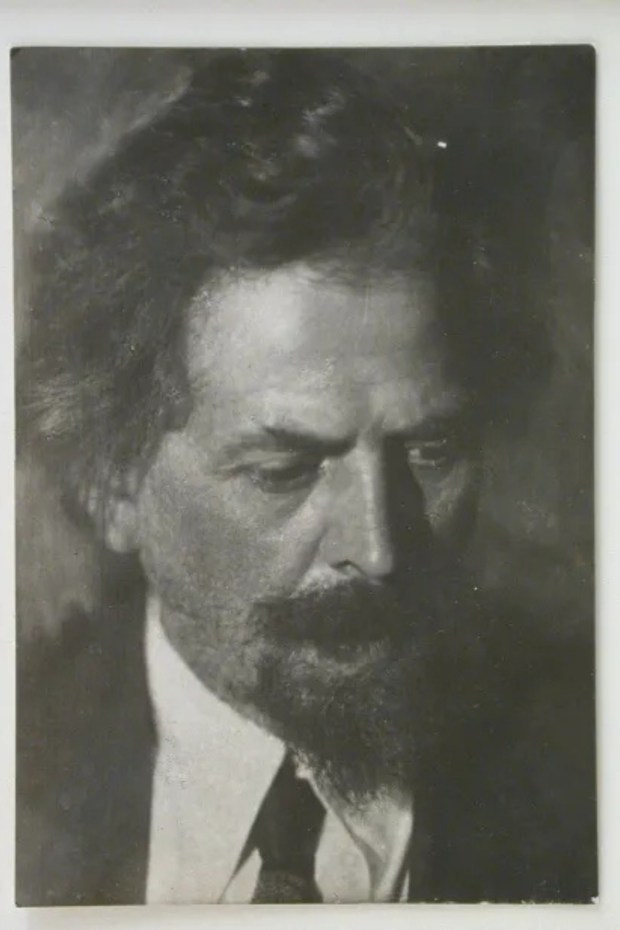

They introduced new spatial standards and helped define a distinct architectural layer—one that linked industrial modernity with everyday life. ‘Azneft’ hired architects from Moscow: Aleksandr Ivanitskii, Aleksandr Vesnin, Leonid Vesnin and Viktor Vesnin to carry out ‘Azneft”s projects fro workers in 1925-1928.

However, the experiment quickly revealed tensions between imported models and Soviet ideological expectations. Critics argued that the house appeared overly comfortable and even luxurious, conflicting with emerging socialist principles that emphasized austerity, collectivism, and the rejection of bourgeois domestic ideals. As a result, the prototype houses in S. T. Razin settlement were seen less as a model to be replicated and more as a lesson in what needed to be adapted—or avoided.

Architects Aleksandr Ivanitskii and the Vesnin brothers responded by reworking American principles rather than copying American forms. They retained standardization, rational planning, and hygienic design, while adapting them to local climate, materials, and socialist ideals. The result became visible in worker’s settlements like ‘Armenikend‘, ‘Belogorod‘ (‘White City’ or ‘Ağ Şəhər’), ‘Montin’, ‘Binagedy’ where housing was integrated with schools, clubs, canteens, and green spaces—designed not merely for shelter, but for shaping everyday life.

Testing Ground for Soviet Housing in Baku

Seen from today’s perspective, Serebrovskii’s American journey was not a simple act of borrowing from the West. It was a process of translation—of technology, finance, organizational models, and even housing types—into a Soviet and specifically Baku context. Oil rigs, credit mechanisms, cottages, and urban form all traveled together. For a brief but decisive moment in the 1920s, the transformation of Baku as a Soviet oil city was shaped by American experience, filtered through one engineer’s conviction that industry, to succeed, must also transform how people live.

Overall, the influence of American housing models on Baku’s oil-worker settlements was real but mediated. This process not only addressed an urgent housing crisis but also contributed to Baku’s role as a laboratory for early Soviet urban and architectural experimentation.

Literature:

Crawford, Christina E. (2022). Spatial Revolution: Architecture and Planning in the Early Soviet Union. Cornell University Press.

Alekperov, Vagit Iusupovich. (2011) Oil of Russia: Past, Present & Future. Minneapolis: East View Press.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy:

- Soviet Architecture in Baku: Why Baku’s Socialist Modernist Buildings Are Must-Sees

- Soviet Mosaics of Baku: Art, Ideology, and Urban Memory

- Mikayil Useynov (Architect)

Written by: Gani Nasirov

City Guide | Writer | Urban Explorer

www.ganinasirov.com