Author: Gani Nasirov | www.ganinasirov.com

Introduction: Soviet Mosaics in Baku

In Azerbaijan, Soviet-era mosaics are more than just decorative fragments of the past. They are monumental works of public art that encapsulate an era’s ideology, aesthetics, and collective memory. Created during the Soviet Union’s golden age of monumental-decorative art (1960s–1980s), these mosaics remain embedded in the architectural and cultural DNA of cities like Baku.

A Brief History of Monumental Art

Since antiquity, civilizations have immortalized their stories through stone, pigment, and structure—from Gobustan’s prehistoric petroglyphs to the intricate mosaics of Rome and Byzantium.

In Azerbaijan, this tradition spans millennia. Examples include:

The Soviet era marked a major shift, bringing monumental art into factories, housing complexes, schools, and public transit systems.

What Are Mosaics in the Soviet Context?

Soviet mosaics used thousands of tiny, hand-cut pieces of colored glass or stone—called smalt—to form large-scale compositions. These mosaics were then installed directly on building facades or pre-fabricated panels. In this way, architecture and visual art became deeply intertwined, creating a cohesive aesthetic experience. This art form helped shape the character of Soviet cities, especially in Azerbaijan during the 1960s and 70s.

In the Soviet context, mosaics served as a powerful propaganda tool, highlighting industrial progress, socialist ideals, and national unity. But beyond ideology, they also brought beauty and personality to otherwise utilitarian Soviet architecture.

Ultimately, mosaics served as a powerful propaganda tool, highlighting industrial progress, socialist ideals, and national unity. Though intended to spread ideology, these mosaics brought color and creativity to otherwise austere and functional architecture.

Khrushchev’s Thaw, Architecture and the Mosaic Renaissance

After Stalin’s death, Nikita Khrushchev promoted fast, affordable housing. The resulting Khrushchyovkas were plain and uniform. Mosaic art emerged to fill this visual and cultural void—adding depth and meaning to concrete surfaces.

Art critic Ziyadxan Aliyev noted that monumental art has the power to shape emotionally resonant urban environments. Azerbaijan’s mosaics are prime examples of this idea in action.

Art Movement called “Severe Style”

The Severe Style marked a shift in Soviet art from idealized, heroic depictions of workers and leaders toward a more raw, realistic, and psychologically nuanced portrayal of everyday life, labor, and emotion. It was still within the limits of Soviet ideology, but it introduced a tone of austerity, honesty, and introspection.

One of the proponents of this style was Azerbaijani Tahir Salahov. While still working within state-sanctioned themes, Salahov presented workers—especially oil workers in Baku—not as perfect heroes but as real, intense, tired human beings. This brought authenticity and grounded the Soviet narrative in more tangible, relatable imagery.

Mosaic Artists: Who they were

Here are a few of those notable Azerbaijani artists who designed and executed monumental mosaics during the Soviet era—true mosaicists who shaped the visual tapestry of Baku. Their mosaics blend folk motifs, local narratives, and socialist-modernist design.

Soviet Mosaics in Baku: Socialist Heritage Sites

1. Baku Metro: Art Beneath the Surface

A. Nizami Station (1976) features mosaics by Mikayil Abdullayev based on Nizami Ganjavi’s literary works. It has transformed the station into an underground gallery which amazes everyday commuters.

B. Artists Arif Aghamalov and Mirzaga Gafarov created mosaics honoring Azerbaijan’s oil workers and industrial heritage at a metro station dedicated to oil workers at Netchilar metro station.

2. Factory and Industry Mosaics

Factories like the Baku Air Conditioner Plant, Baku Wine Factory and many other industrial sites used mosaic panels to elevate industrial sites into spaces of cultural expression.

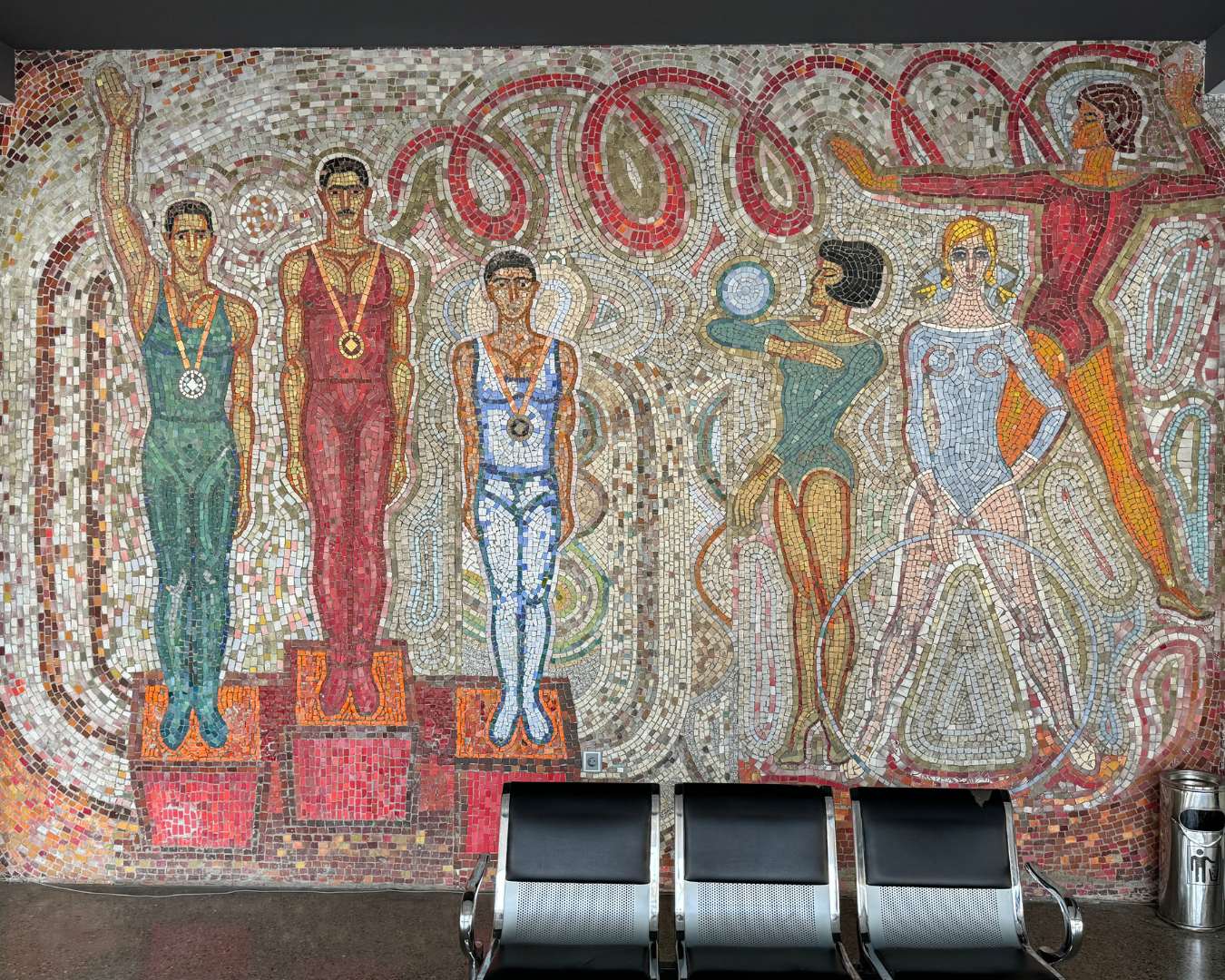

3. Sports and Health Centers

Buildings like the Heydar Aliyev Sports Complex, Baku State Circus and even Universities were adorned with vibrant mosaics promoting healthy lifestyles and community spirit.

4. Public parks, Cultural and Civic Landmarks

Mosaic of “Worker’s Hands” is a striking mosaic tucked away in a quiet corner of Bayil. This mosaic powerfully symbolizes the dignity of labor and collective strength through an image of monumental hands cradling industrial extraction of crude oil.

Themes and Symbolism in Soviet Mosaics

The mosaics of Soviet Azerbaijan portrayed a wide range of symbolic content, including:

- Labor and Progress: Workers, farmers, builders, and scientists as central heroic figures

- Health and Athleticism: Scenes promoting wellness and fitness

- Peace and Unity: Brotherhood of nations and ethnic harmony

- Science and Space: Rockets, satellites, and stars as symbols of progress

- National Identity: Azerbaijani ornamentation, folk motifs, and historical figures

Legacy and the Case for Preservation

These mosaics were not merely state propaganda—they were public art installations, urban design tools, and cultural reflections embedded in the everyday lives of Soviet Azerbaijani citizens. Today, many are deteriorating or vanishing, victims of neglect, weather, and aggressive urban redevelopment.

Yet, they remain critical to understanding 20th-century Azerbaijani identity. These artworks are visual storytellers, narrating not just ideology but also craftsmanship, aesthetics, and the cultural ambitions of an era. They deserve preservation—not just in museums, but in their original public contexts, where their interaction with architecture and community can still be felt.

Fortunately, efforts are underway to document and protect these mosaics:

On the institutional front, IDEA Public Union in Baku has launched an official initiative to restore and conserve public mosaics, as reported by Azertag. This is a promising step toward safeguarding these urban artworks for future generations.

The Instagram project Mosaics of Azerbaijan, initiated by Mehrin Alili, highlights endangered works across the country. Alili also co-authored a key article on the subject, “National Form, Socialist Content: Contributions of Azerbaijani Mosaicists to Soviet Monumental Art”, providing valuable academic insight into the unique character of Azerbaijani mosaics.

Writer and researcher Vahid Shukurov has also contributed significantly to public awareness through his detailed articles on the topic, such as this one on Azerhistory, which examines the mosaics in their historical and aesthetic context.

Together, these grassroots efforts, scholarly work, and institutional backing form a growing preservation movement—one that recognizes these mosaics not as relics, but as living cultural heritage.

Conclusion

The Soviet mosaics of Azerbaijan are a vibrant part of the country’s architectural and cultural history. They are expressions of artistry, ideology, and identity—etched in stone and glass across factory walls, metro stations, and city streets.

As we modernize our cities, let us also protect these fragments of history—so that future generations can read the stories embedded in the walls of Baku.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy:

- Soviet Architecture in Baku: Why Baku’s Socialist Modernist Buildings Are Must-Sees

- Legacy of Soviet Architecture in Baku: A Brief Historical Insight

- Mikayil Useynov (Architect)

Written by: Gani Nasirov

City Guide | Writer | Urban Explorer

www.ganinasirov.com