Author: Gani Nasirov | www.ganinasirov.com

Introduction

Baku, a city with rich history and culture, bears the indelible mark of the Soviet era. This period, particularly the mid-20th century, witnessed a significant architectural movement known as Socialist Modernism. Emerging in the mid-1950s and lasting until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Soviet Modernism reshaped the urban landscape of Baku, leaving behind a fascinating legacy of socialist/communist ideology.

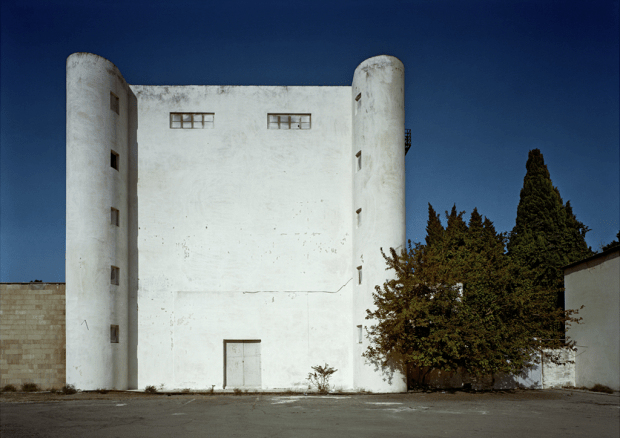

Socialist Modernist architecture in Baku is characterized by its functionalist approach, clean lines, and emphasis on mass housing and public spaces. Inspired by the ideals of the Soviet state, architects sought to create buildings that were not only aesthetically pleasing but also practical and affordable. The result is a unique blend of Soviet ideology and international modernist trends, resulting in a distinctive autochthone architectural style (1970s) that continues to captivate and intrigue.

In the following sections, we will delve deeper into the key characteristics of Socialist Modernist architecture in Baku, explore iconic examples of this style, and discuss its lasting impact on the city’s urban environment.

Brief survey of Soviet Architecture in Baku

Constructivism was a popular and flourishing modern architecture movement in the 1920s and the early 1930s in the Soviet Union. It combined technological innovation with a Russian Futurist influence, resulting in stylistically abstract geometric masses. It aimed at serving to meet the needs of changes in society of the time: a revolutionary society producing a revolutionary architecture.

One of the pioneering architects who was practicing constructivism in Baku was the Vesnin brothers. Their first materialized constructivist project was built as workers’ town in Baku in 1925. Many other Azerbaijani architects, too, embraced constructivism in their early careers.

In the mid-1930s, Constructivism fell out of favour and the Soviet leadership backed a policy of return to national traditions and roots. The architecture of this era is more known as the Stalinist Empire Style or Socialist Realism. In Azerbaijan, it produced a new wave called National Romanticism (an umbrella term to reflect on traditional and historically Azerbaijani national aspects of architecture in Stalin’s Era) with the integration of ethnic elements i.e. Islamic traditions of art and design. This architecture advocated the adoption of decorations, ornaments and tall and larger arch-ways that rooted in Oriental and Azerbaijani culture. Leading architects of this movement in Azerbaijan were Mikayil Useynov and Sadig Dadashov.

The era of 1955-1991 radically changed the approaches to architecture and in particular urban planning. Rooted in the Russian avant-garde (Constructivism), Socialist Modernist architecture primarily oriented with utilitarian purposes whereas decorations and ornaments on buildings were rejected. Advanced methods and modern technologies required to boost industrialization and cost reduction. This is when massive, grey, tall, austere match-boxes appeared in the built environment of Baku. The notable projects of this era are Baku’s Microraions residential complexes and many other administrative office buildings, cultural and convention centers.

Elusive definition of Socialist Modernism

The term “Socialist Modernism” is a complex and often contested concept. While it is frequently associated with the architecture of the Soviet Union and its satellite states in the mid-20th century, its scope is broader. It encompasses a range of architectural styles and movements that emerged in various contexts from the late 19th century onwards.

Despite its broad scope, Socialist Modernism is often linked to the modernist movement, which dominated architecture from the late 19th and through the 20th century. This connection is particularly evident in the Soviet Union, where modernist principles of functionalism, rationalism, and industrialization were embraced and adapted to serve the goals of the socialist state. However, the Soviet interpretation of modernism often diverged from Western trends, resulting in unique and often experimental architectural forms.

Nonetheless, scholars have increasingly sought to integrate Soviet and Eastern European architecture into the broader narrative of global modernism in recent years. By examining the work of individual architects, the role of international organizations, and the exchange of ideas and technologies, researchers have highlighted the interconnectedness of architectural developments across different regions and political systems. This approach has led to a more nuanced understanding of Socialist Modernism and its place within the history of 20th-century architecture.

For those who want to delve into the fascinating world of Socialist architecture without wading through dense academic prose, there are several engaging options. Resources like the Instagram accounts “Socialist Modernism” or “BRUTgroup” offer a visually appealing entry point. These accounts prioritize stunning visuals, allowing viewers to appreciate the aesthetics without getting bogged down in the academic jargon.

Exhibition catalogues are another excellent way to combine stunning photography with expert analysis. The Museum of Modern Art in New York, for instance, hosted a captivating exhibition titled “Lost Vanguard: Soviet Modernist Architecture, 1922–32 Photographs by Richard Pare” or another exhibition project by Georg Schöllhammer tilles “Soviet Modernism 1955-1991: Unknown Stories”. They provide insightful essays alongside stunning photographs, allowing viewers to learn and appreciate the architecture on a deeper level.

By exploring these resources, we can gain a clear understanding of the various terms and periods associated with Socialist architecture. This approach helps us understand Socialist Modernism not as a singular style, but as a fascinating chapter within the global story of 20th-century architecture.

Socialist Modernism in Baku

The starting point for the Socialist Modernist Movement in architecture is the speech by Nikita Khrushchev at the closing of the All-Union Builders’ Conference on December 7, 1954. The essence of the Soviet architects’ creative focus has been reshaped for the decades to come until 1991.

The main objectives put before architects were to find a solution to housing problems of Soviet families and the solution had to be accomplished economically. This in return led to mass production and reproduction of prefabricated standard apartment blocks in residential complexes known as Microraions.

These kind of apartment blocks were already experimented in 1920s as worker’s residential settlements. “The distinctly Constructivist Armenikend test block (1925-27) … marks the birth of the socialist residential superblock, a persistent planning model throughout the Soviet period because it took full advantage of socialist land ownership structure and was agnostic about architectural language. Both the Stalinist-era kvartal and the Khrushchev-era microraion—installed pervasively throughout Soviet space—owe a debt of precedent to the Armenikend test block.”

Prefabrication and industrialization of construction and architecture brought up an approach of economical and quantitative production of the houses. Some argued it made cities monotonous, derivative and unexpressive. The individual approach to finding architecture solution has been replaced with mass production, aesthetic beauty dumped in favour or utilitarian and functionality. These had limited and restrained the potential of architects in the Soviet Republics in many ways.

Nonetheless, proponents of Socialist Modernism argue that the microraions are not what it should be judged by. The distinctive work with the best practices through plasticity, transparency, airiness, spatial complexity, innovative methods of using contemporary materials, refinement of details, novelty and abstract imagery, and beauty of contrasting forms are the value and the landmark designation of the Socialist Modernism.

The architecture served for political purposes. Therefore, Soviet leaders, from Stalin to Khrushchev and Brezhnev, articulated visions for architecture. They had prioritized functionality and served the needs of the working class. While Stalin’s era emphasized grandiose Stalinist architecture, Khrushchev’s period ushered in a more austere and functionalist approach.

However, it was Brezhnev’s era that saw a relative relaxation of strict architectural guidelines, allowing for greater creative freedom. This period, particularly the 1970s and 1980s, witnessed the emergence of a distinct “autochthon” style of Socialist Modernism in Baku. This style, characterized by a blend of Soviet functionalism and local Azerbaijani architectural traditions, resulted in unique and often experimental buildings.

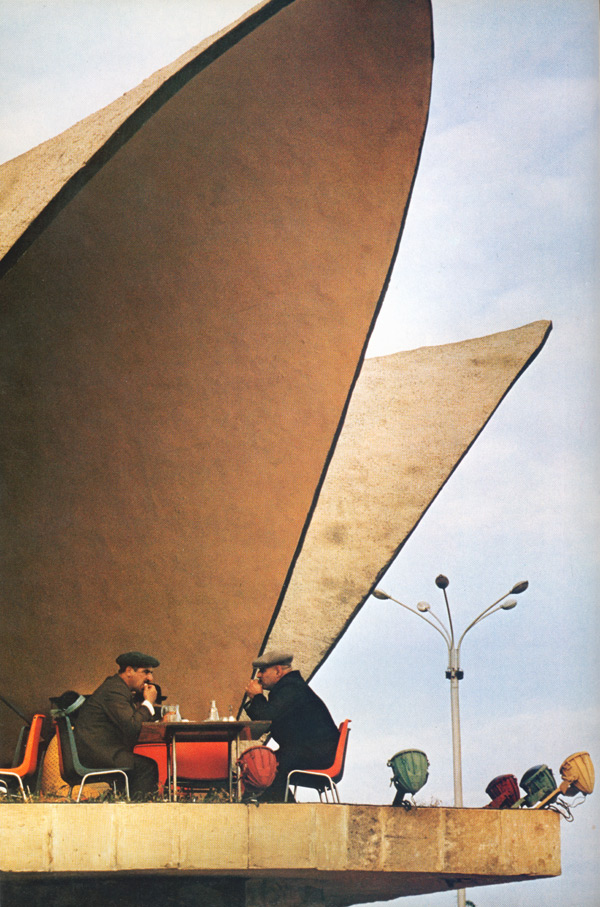

Baku has those iconic landmarks representing Socialist Modernism Architectures that deserve publicity, acclaim and praise. Even, there a few experimental residential apartments that exceptionally stands out, whereas most of the masterpieces are public buildings as administrative offices, sport complexes, concert halls or hotels.

Microraions

Microraions, self-contained residential complexes, were a hallmark of Soviet urban planning in 1960s. These neighborhoods, designed to house 5,000 to 10,000 people, aimed to create self-sufficient communities with all essential amenities within walking distance.

The first Microraion was built in 1957-1958 in Baku. This process has also intensified by opening Baku House Construction Factory (an industrial business conglomerate) in 1960. The early prefabricated residential complexes were 5-story houses (aka Khrushchevka). 9-story prefabricated houses were built from the 1970s and onward. 9-story prefabricated houses (aka Brezhnevka) massively built in Ahmadli and Guneshli (to the east of Baku) and 8th Microraoin (to the north of Baku).

Nine Microraions had been built on the outskirts, mainly in direction to the north and east of Baku’s historic core during this period. This expansion, eventually to the birth of new term in urban planning literature, the ‘Greater Baku’.

Each Microraions typically included a mix of residential buildings, schools, kindergartens, shops, clinics, and recreational facilities. The goal was to minimize the need for residents to travel outside the neighborhood, promoting a sense of community and convenience. The design often prioritized efficiency and standardization, with large, uniform apartment blocks and a grid-like layout.

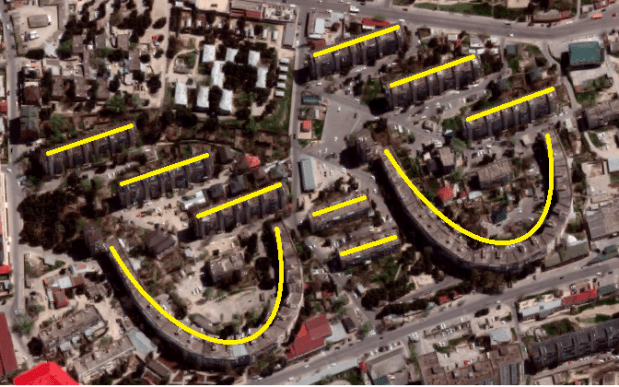

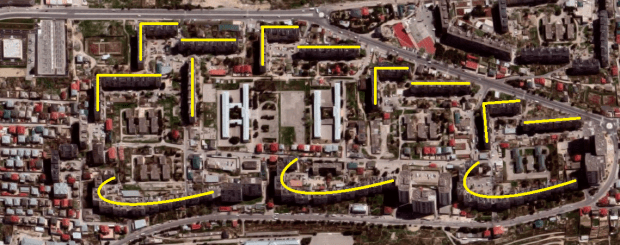

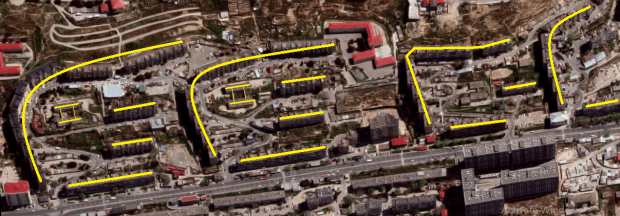

The residential developments in Ahmadli plateau has produced some mesmerizing shapes. It could have been a deliberate planning as it stand out in sheer contrasts to planning in most of the soviet residential developments. It could also be partly due to specifics challenges of the landscape which allowed the planners to come up with creative solutions challenges arised from complexity of the landscape.

While Microraions provided a solution to rapid urbanization and housing shortages, they also faced criticism for their monotony and lack of individuality. The emphasis on functionality sometimes overshadowed aesthetic considerations, leading to a somewhat uniform and impersonal urban landscape. However, these neighborhoods played a significant role in shaping the urban expansion of Baku.

Design & Art Institutions

“Azerdovlatlayihe”, Azerbaijan State Design Institute formerly known as “Azgosproekt” was country-wide main industrial and civil engineering design institution. Established in 1926 as a construction department, the institute has evolved into a leading platform for the design of state facilities. Renowned architects have contributed to its legacy, and numerous buildings and structures stand as testaments to their work. It has been restructured as the State Committee on Urban Planning and Architecture of the Republic of Azerbaijan today.

The Baku State Design Institute (formerly known as Bakgiprogor) was established in 1937 as an architectural and planning bureau under the Executive Committee of the Baku City Soviet of People’s Deputies. Since 1952, it operated as a design institute under the names of “Bakproyekt” firstly and later of “Bakgiprogor”, focusing on the planning of Baku city and the design of civil and residential buildings. The institution has known for its multinational working staff of the institute who had played a pivotal role in shaping the city’s urban environment.

Monumental Art: Mosaics

Starting from 1960s, monumental art in particular mosaics became one of the defining features of urban architecture. As an integral part of Soviet design, they adorned the facades of public buildings, cultural institutions, and even residential complexes. They were used to create monumental panels celebrating the achievements of the Soviet people and commemorating significant historical events.

Mosaic compositions could be found on the facades of cultural centers, cinemas, schools, kindergartens, factories, and other structures. Mosaics also played a crucial role in the design of metro stations, creating a distinctive ambiance and emphasizing the grandeur of underground architecture. Numerous mosaic panels decorated sports complexes, stadiums, and health centers, inspiring citizens to embrace a healthy lifestyle.

Soviet mosaics became iconic symbols of their time, reflecting the ideals and aspirations of the nation. They served not only as decorative elements but also as powerful tools of propaganda, shaping public consciousness and fostering patriotic sentiment.

Socialist Modernism in Popular Culture

While acclaimed globally, Socialist Modernism faces domestic challenges in the post-Soviet states. The complex politics of the Soviet past and rising nationalism have sparked debates about whether Socialist Modernism is a national heritage worthy of protection or a foreign influence to be rejected. This debate varies across former Soviet republics, but in Baku, it is less prominent and often intertwined with broader urban development initiatives aimed at improving the built environment.

It is difficult to assign romantic-national qualities to Socialist Modernism to garner popular support for its preservation. However, the emergence of local modernist trends, such as the autochthon style in the Caucasus, demonstrates a unique regional interpretation of Socialist Modernism. Elchin Aliyev even identify a distinct period of “Baku Socialist Modernism” between 1975 and 1985. These elements suggest that Baku can claim a certain ownership of its Soviet architectural heritage.

Despite these nuances, the ideological underpinnings of Soviet Modernism remain a significant challenge. The communist past of countries like Azerbaijan is often selectively rejected, making it difficult for Socialist Modernism to find its place in national heritage politics.

In post-Soviet Baku, the situation for Soviet-era architecture is dire. The built environment from 1955 to 1991 is rapidly deteriorating, and there are few policies in place to preserve it. The construction boom since 2006 has further overshadowed Soviet-era architecture, with many examples being lost to development.

While a few dedicated architects are working to raise awareness and influence decision-makers, a widespread sense of nostalgia for Soviet Modernism persists. This nostalgia is often linked to the iconic, yet often criticized, “microraion” residential complexes. These massive, rectangular apartment blocks evoke a melancholic and sometimes even depressive atmosphere, reflecting the complex emotions associated with the Soviet past.

Conclusions

Socialist Modernist architecture in Baku, a product of the Soviet era, offers a unique blend of functionalism and aesthetics. This style, characterized by clean lines, geometric forms, and emphasis on mass housing, shaped the city’s urban landscape in the immediate neighborhoods of Baku’s historic core, Icherisheher (Old Town). While it faced challenges, including the monotony of mass housing and the ideological baggage of the Soviet past, it also produced iconic landmarks that continue to captivate. As Baku evolves, preserving and appreciating its Socialist Modernist heritage is crucial to understanding its rich architectural history and unique identity.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy:

- Soviet Mosaics of Baku: Art, Ideology, and Urban Memory

- Legacy of Soviet Architecture in Baku: A Brief Historical Insight

- Mikayil Useynov (Architect)

Written by: Gani Nasirov

City Guide | Writer | Urban Explorer

www.ganinasirov.com